Florabank Resources

Because of the increased inter- est to conserve a wide range of species, including forestry spe- cies, the need to know how to handle and conserve the seeds of a given species in an optimum and cost-efficient way has be- come very pertinent. It is hoped that this publication will help genebank staff and other scientists in their duties to conserve the dwindling resources in a more secured and effective way.

Regional_Guidelines

Tree to 30m high in forests and along watercourses or shrub on drier sites. Bark usually smooth (fissured at the base of old trunks only), grey-green or dark grey to almost black. Branchlets often glaucous. Leaves bipinnate, usually bluish-grey with 10-30 pairs of pinnae and a gland at the junction of each pair of pinnae.

Regional_Guidelines

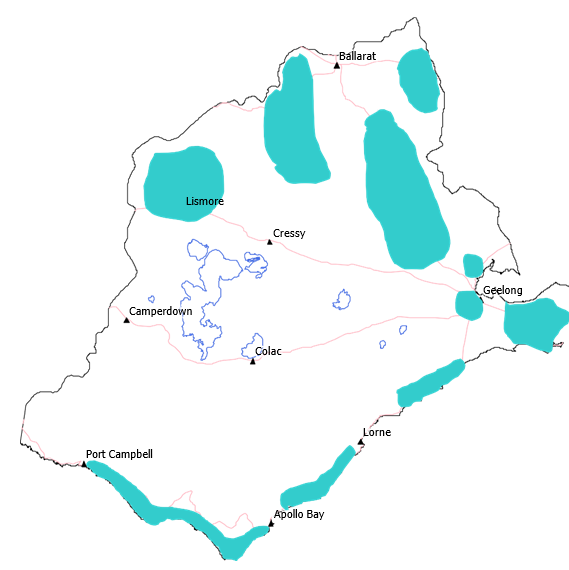

This guideline is intended for those who are involved in indigenous seed collection and the coordination of indigenous revegetation projects within the Corangamite region. It explores a comprehensive method of assessing plant species, given our current understanding, to give clear seed collection ranges that will guide best practice. By providing these guidelines, it is hoped that improved seed collection methods will be adopted to maintain the genetic diversity of precious remnants, individual species and revegetation projects.

Technical

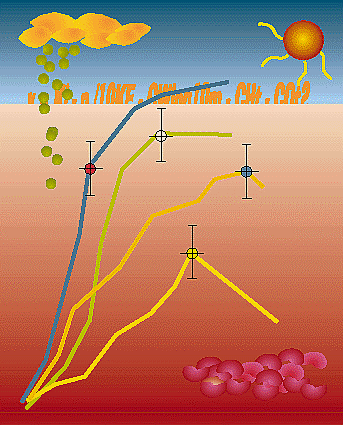

Direct seeding is a common and important revegetation practice used throughout temperate Australia. This report examines the effect of direct seeding at different times of the year on germination and survival of native tree and shrub species at two sites. The trials showed that some species have better survival when sown in a particular season. This has implications for direct seeding practitioners, who need to make regular observations of their own sowings to determine the preferred season for the species that they use.

Technical

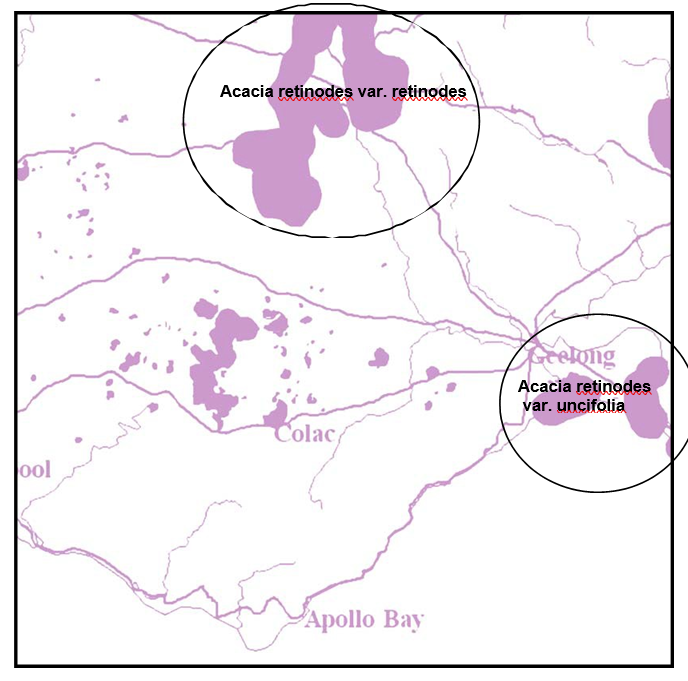

Short-lived perennial. Common Names: Wirilda, Swamp Wattle, Silver Wattle (ANBG n.d.) MORPHOLOGY: Shrub or small tree 5–10 m high. The branchlets are sometimes pendulous, often angled or flattened, and glabrous (not hairy).

Regional_Guidelines

This fact sheet describes the set-up and use of a propagation igloo as a low cost seed drying method that will work anywhere in Australia. Such igloos are already used by some seedbanks and others use greenhouses and similar structures for the purpose.

General

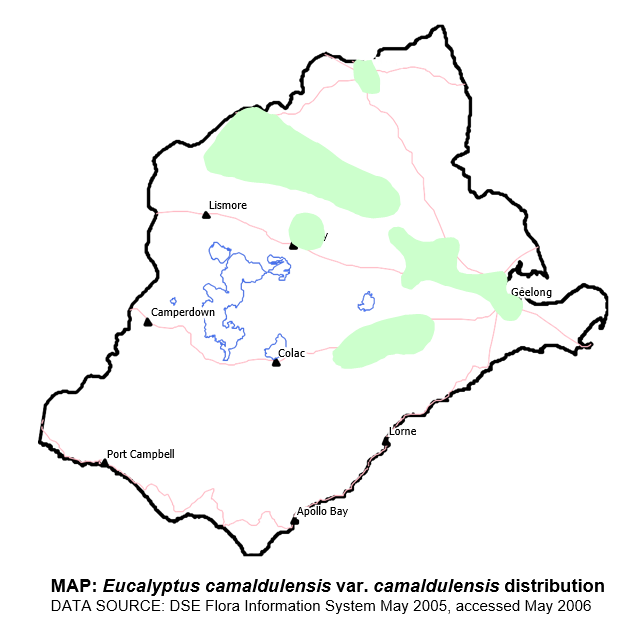

Long lived woody perennial. Common Names: River Red Gum, Murray Red Gum, Red Gum, River Gum. MORPHOLOGY: Tree to 40 m tall. Bark smooth, mottled, shedding at intervals throughout the year to show white, yellow and grey, becoming rough around the base.

Regional_Guidelines

Victorian eucalypts are currently under review by taxonomist Kevin Rule (K. Rule 2005 pers. comm.). Common Names: Yellow Gum (preferred name), White Ironbark, South Australian Blue Gum (ANGB n.d.) MORPHOLOGY: Mallee or tree to 25 m tall. Bark at base usually coarse, loose, fibrous with most of trunk or stems smooth and yellowish.

Regional_Guidelines

A survey of collection, storage and distribution of native seed for revegetation and conservation purposes - The major focus of the report is on community-based seed operations that support revegetation and landcare initiatives, but the report broadly describes the collection, storage and distribution of native plant seed for revegetation purposes across Australia.

Reports

Seed Production Areas (SPAs) are one solution to the increasing demand for native seed for revegetation. Although genetic issues are critical to the success of SPAs, they are often perceived as complex and difficult to understand. The goal of this brochure is to help you understand the main genetic issues associated with SPAs.

General

FAO and IBPGR have been cooperating since the early seventies to strengthen national capabilities in ex situ conservation of plant genetic resources, including the development of agreements and network activities with institutions that had accepted primary responsibility for long-term conservation of germplasm of particular species in their base collections.

Technical

It is a widely held assumption that plants used in revegetation projects should be derived from "local provenance" seed. Throughout the last twenty years or so this notion has been a central tenet of the extension literature in government funded natural resource management programs such as Landcare. On the whole I believe this assumption is based on unjustified and tenuous interpretations of the related scientific literature.

Technical

Long-lived perennial Common Names: Drooping She-oak, Coast She-oak, Hilloak; also various spelling variations such as She Oak, Sheoak, She oak, She-oak

Regional_Guidelines

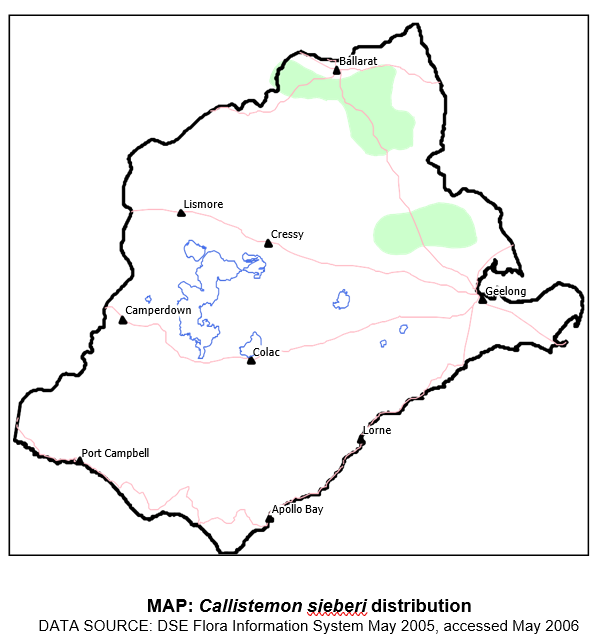

Shrub or small tree to 3 m high; bark hard, and fissured on old plants. Branches slightly weeping on mature plants. Leaves variable, narrowly oblanceolate

Regional_Guidelines

An alternative to mechanical sowing is the hand or “niche” sowing technique. This involves little in the way of soil disturbance and allows for more controlled placement of plants within a site. Hand sowing is also useful for smaller revegetation jobs, on steep slopes and in areas where machinery cannot or should not go. Depending on the locations and methods used, hand sowing is as efficient as other planting methods. As a guide, 800 to 1500 plants can be sown per day per person and trials indicate that a 90% success rate is achievable for some species.

Technical

A number of recent publications in the list at the end of this article provide detailed information on the subjects of seed collection, storage and handling. Most of the listed references are books or review articles which provide many other original references on these subjects. Rather than paraphrasing these references, most of which are readily available, I have listed below in point form the areas that should be considered, and indicated which references relate to each area.

Technical

The increased use of direct seeding techniques in the revegetation industry has created a demand for diverse, provenance based indigenous seed. Seed is currently supplied foremost from roadsides and private property. With a high demand and seasonal impacts causing poor or reduced seed set, supply is often limited and labour intensive to collect. Collection often needs to be timed carefully to capture seed from some species which may drop seed quickly.

General

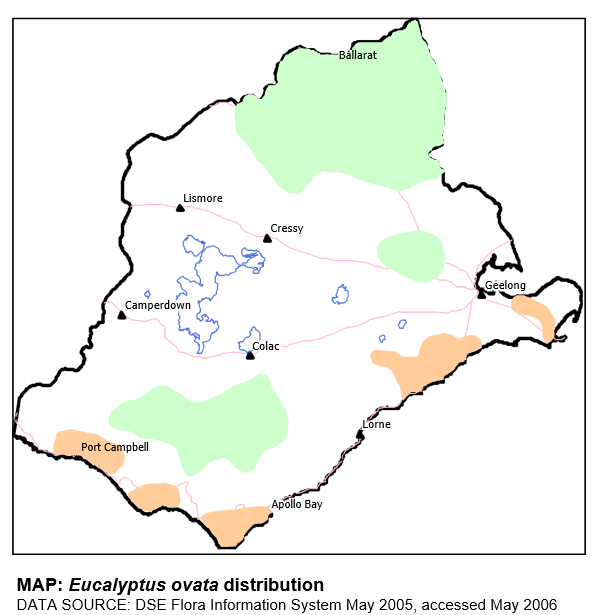

Long lived woody perennial. Common Names Swamp Gum, White Gum, Black Gum, Blue leaved Sally, Marrawah Gum (ANBG n.d.) MORPHOLOGY Tree to 20 m tall, bark varies from smooth throughout to rough and loose over most of the trunk.

Regional_Guidelines

The FloraBank project seeks to improve the availability and quality of native seed and plant material for revegetation and conservation purposes in Australia. It provides support, advice and assistance to collectors, seedbank managers and distributors of native seed and plant material. FloraBank seeks to enhance existing networks between seedbanks and plant collections . The project will assist with training and provide guidelines for the collection, storage and handling of seed to local, regional and community-based seedbanks and groups. FloraBank encourages practices that protect Australia's biodiversity.

Reports

Seed Production Areas (SPAs) are areas where native plants of known seed source are grown to produce seed. This can be done using a horticultural type method or as part of a mixed biodiversity planting. Greening Australia (GA) is encouraging and assisting landmanagers to establish SPAs to bolster the supply of understorey species and complement the seed sourced from wild populations or Seed Collection Areas (SCAs).

General

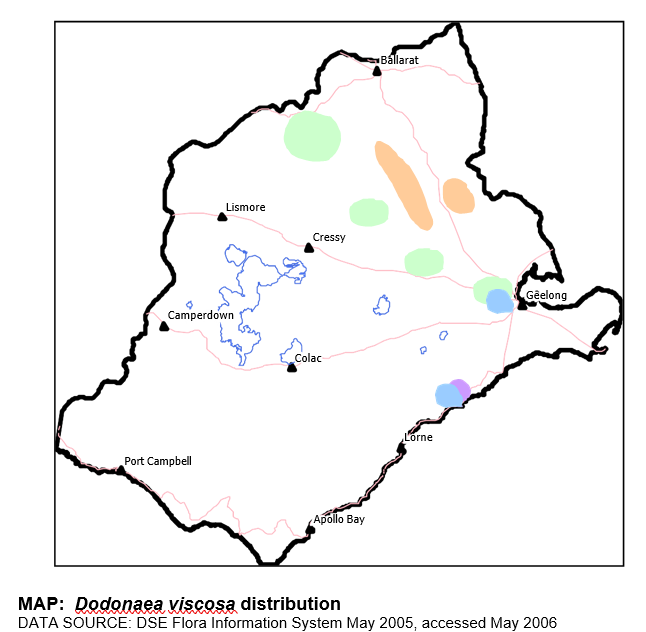

Long lived woody perennial. Common Names: Sticky Hop-bush, Giant Hop-bush, Broad leaf Hopbush, Candlewood, Narrow leaf Hopbush, Native Hop, Native Hop Bush, Soapwood, Switchsorrel, Wedge leaf Hopbush

Regional_Guidelines

This document presents some case studies included in the pages from Corangamite Seed Production Area Guidelines. Information compiled for this note series was a result of extensive literature reviews, plant record searches and personal communications completed by Simon Heyes, Michelle Butler, Christine Gartlan and Anne Ovington

Regional_Guidelines

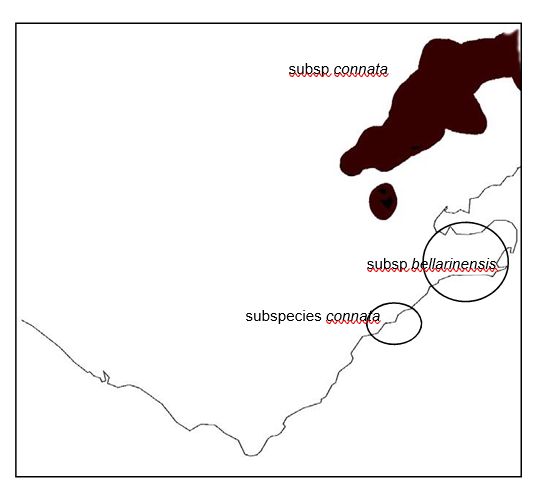

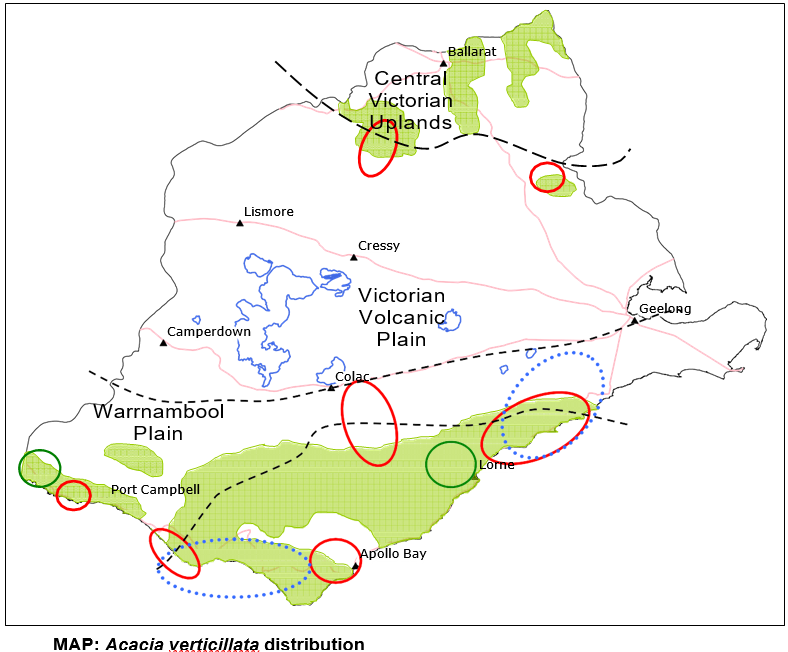

Long lived woody perennial Common Names: Prickly Moses, Prickly Mimosa (ANBG n.d.) MORPHOLOGY: Spreading shrub or tree to 10 m high. This is a very complex, variable species with four subspecies currently recognised. Some of these subspecies occur in the same geographic area, and intermediates may be present

Regional_Guidelines

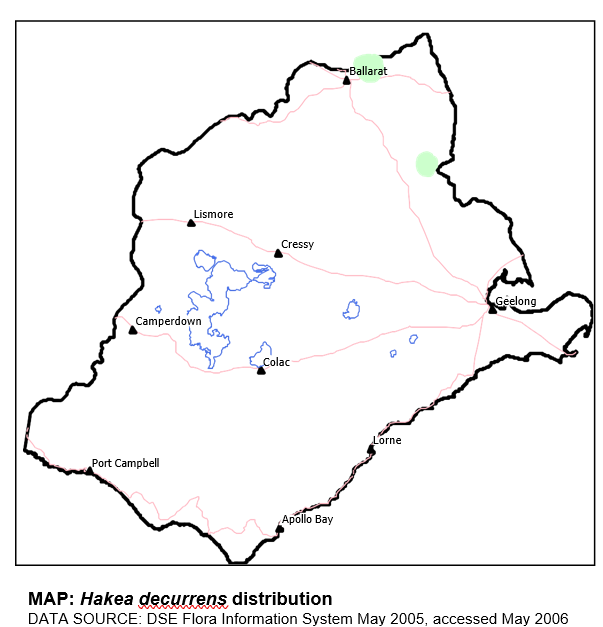

Long lived woody perennial. Common Names Bushy Needlewood (Walsh & Entwistle 1999), Silky Hakea (GAV n.d.). MORPHOLOGY Shrub or small tree 0.3-4m high, sometimes lignotuberous.

Regional_Guidelines

This project aimed to provide information enabling revegetation providers and commercial forestry operations across Australia to improve on-the-ground establishment outcomes. Through experiments, data collection, modelling and community consultation, it has identified key strategies that reduce the risk of establishment failure from adverse climatic conditions. These are dominated by the primary strategy of ensuring adequate initial (at-planting) soil moisture via effective forward- planning and site management.

Reports

Long lived woody perennial. Common Names: Lightwood, Hickory Wattle, Broad-leaf Wattle, Sally Wattle, Scrub Wattle, Black Wattle

Regional_Guidelines

Australian Native Vegetation Assessment 2001 is the first assessment of the extent of Australia’s major native vegetation types. It is an Australia-wide assessment at the regional scale and is based on the National Vegetation Information System—an agreed framework for collating and presenting information on Australia’s vegetation.

General

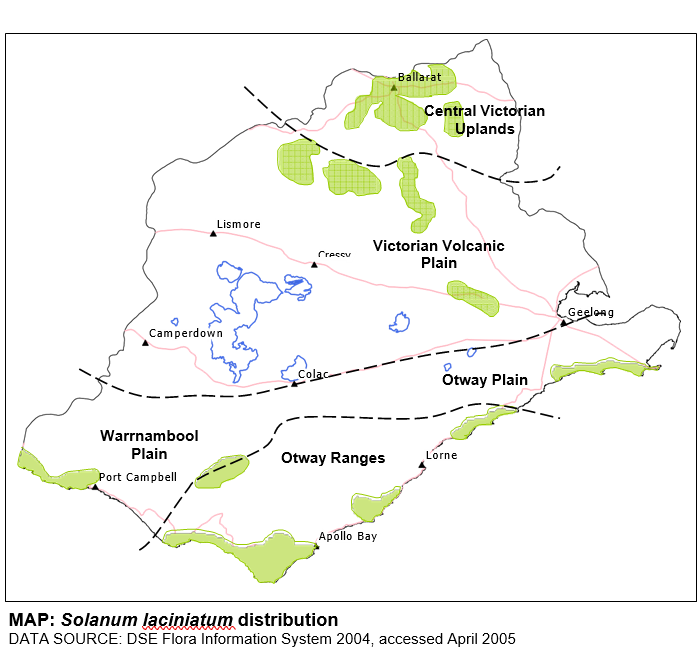

Long lived woody perennial Common Names Kangaroo Apple (Bonney 2003), Large Kangaroo Apple (Walsh & Entwisle 1999), Cut-leaf Kangaroo Apple (GAV n.d.) MORPHOLOGY Erect shrub to 3m high, green, often with purplish stems, branches and stems smooth except for minute hairs on young growth, prickles are absent.

Regional_Guidelines

Seed drying and extraction involves the removal of seed from the fruit following collection. These processes should be carried out as soon as possible after collection and care must be taken to avoid any damage to the seed, which may reduce viability and longevity. Seed is rarely fit for immediate storage following collection, requiring either drying or de-pulping, extraction from the fruit and further cleaning. The methods for drying and extraction are many and varied and depend very much on the type of fruit, seed and equipment available.

General

We all know that revegetation is needed, the question is what do we mean when we say revegetation, is it plantations of trees? or is it reestablishment of vegetation?

General

Long lived woody perennial. Common Names: Blackwood, Paluma Blackwood, Hickory, Sallow Wattle, Sally Wattle, Black Wattle

Regional_Guidelines

This paper presents some of FloraBank’s findings about the way native seed is collected, stored and handled at the community level. Based on our experiences and the close relationship between FloraBank and the Bushcare Support network, this paper also provides insights into community issues and attitudes to the availability and quality of native seed for revegetation and conservation purposes.

Reports

Long-lived woody perennial. Common Names: Silver Banksia, Honeysuckle, Warrock. Shrub or tree up to 12m high, with or without lignotuber.

Regional_Guidelines

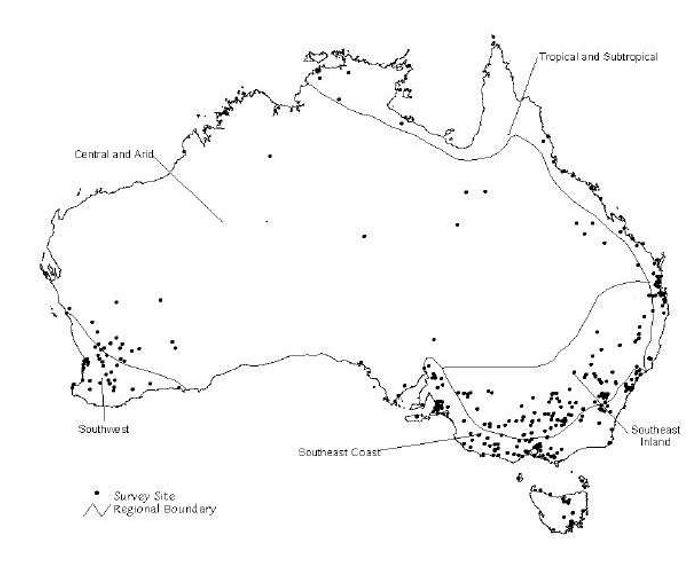

This report presents the results of a national survey conducted by FloraBank and Greening Australia in May 1999. The survey focused on the use of native seed and seedlings1 by people directly involved in revegetation at the community level and their expectations of demand and supply. It builds on the results of previous consultation and survey work by FloraBank to complete the picture about native seed as it is collected, stored and used for revegetation work in Australia.

Reports